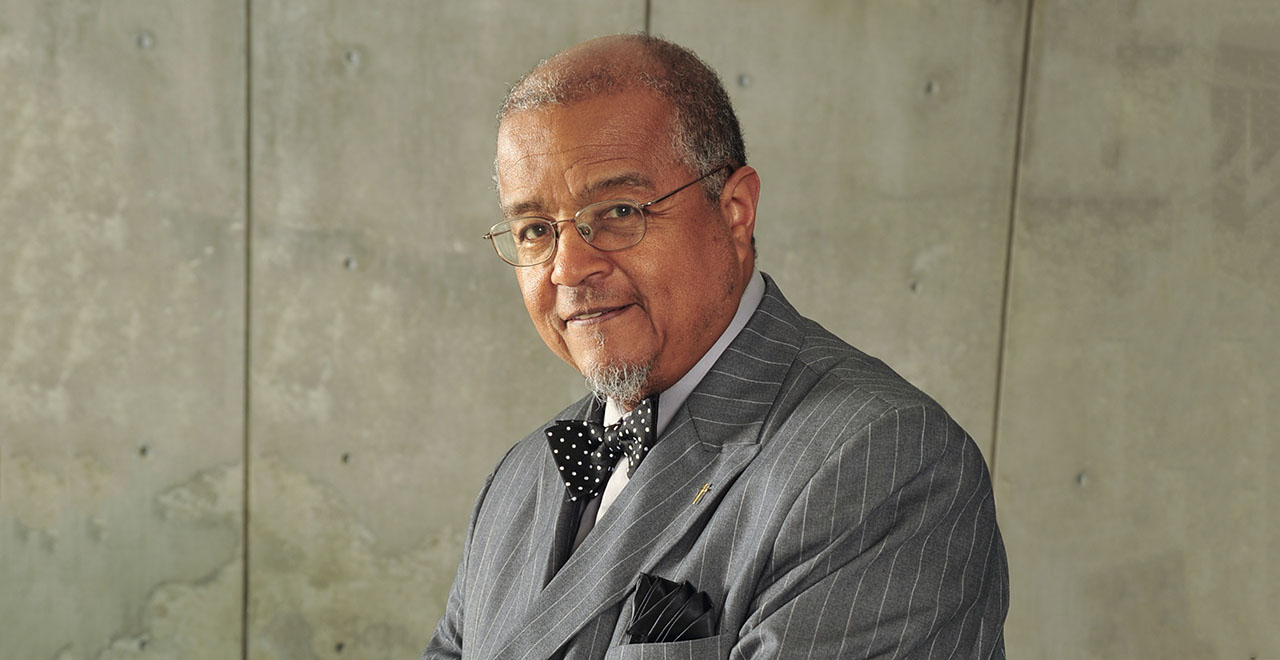

Rev. Dr. Forrest M. Pritchett

Rev. Dr. Forrest M. Pritchett

Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ

Director, Martin Luther King, Jr. Leadership Program

Senior Adviser to Provost on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Published in March 2022

Rev. Dr. Forrest M. Pritchett, more commonly addressed as Rev. Pritchett, is a long-time civil rights activist, mentor, and adviser. With 53 years of experience in higher ed, including his over 40-year career at Seton Hall, which began in 1978, he currently serves as the director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Leadership Program and the senior adviser to the provost for diversity, equity, and inclusion. Throughout his years at Seton Hall, he has functioned as the assistant dean of the Black Studies Center, a faculty mentor in Freshman Studies, an adjunct professor in the departments of Africana, Interdisciplinary, and Religious Studies, and the program director of the Seton Hall Gospel Choir. He is known well for coordinating the annual MLK, Jr. Day Symposium, which provides perspectives on racism, privilege, and justice while educating students on the principles of MLK as a civil rights leader. He has seen initiatives like the Martin Luther King, Jr. Scholarship Association grow immensely, now supporting up to 20 students each year financially. As someone who has inspired generations of Pirates through his many roles, and has contributed greatly to numerous campus organizations, the University continues to embrace Pritchett as a servant leader and a pillar amongst the campus community that has helped to challenge the University to be and do better.

Getting to sit down with Rev. Pritchett was an honor. I wanted to hear more about how he began his activist work. He took me back about 62 years. It was February 1st, 1960, and a young Pritchett in his junior year of high school returned home from track practice to catch the evening news. Engrossed in a segment where he saw four Black college students sitting down at North Carolina A&T, he thought in fear that the men could get themselves killed. Just a few months later, he was following the presidential campaign between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy and learning for the first time about Catholic bias. "These are the things that helped me make decisions. I could have ignored all of that kind of stuff, but nobody else was talking about race. Everyone wanted to avoid the issue," he said. "When I left Atlantic City High School in 1961, I don't think anyone saw me as a leader." These were just some of the events that would inform how he viewed the world for this rest of his life.

He added, "It's like God knew what plans He had in store for me." Recalling again when he was a junior, he remembered a guy who lived on his block that attended Seton Hall and was on the track team. Every weekend the guy would drive back home to Atlantic City. Upon arriving, he'd ask Pritchett to change into his track gear to go run. "While we're running and practicing, he would explain to me what it means to be a Negro at an all-White school," Pritchett said. "I did not aspire to be a college professor or anything. If someone asked me, I probably would've said I'd like to be a guidance counselor, but that's how I got introduced. It took me years before I made that connection, but he was mentoring me, and I had no idea what my future would be."

Once Pritchett entered Delaware State University as a freshman, it was almost as if his tie to race relations was inevitable. The disparities between himself and his White classmates were ever fixed and pronounced. In the week leading up to his first semester, Pritchett and a few other freshmen spent a Saturday touring downtown Delaware. Stopping around noon to grab a bite to eat, they were greeted by a waitress who told them they'd have to take their food in a bag and go outside. "She wasn't nasty at all. She was nice, so we thought it was a joke," he laughed. "But it wasn't." Pritchett and his classmates returned to campus and had a rally to complain about what had just taken place. Although 100 students agreed to take action, only seven showed up to participate in what would be Pritchett's first sit-in demonstration, which resulted in him being arrested. "All of a sudden, those kinds of things propelled me to be the role model. I did not do it for the popularity. Stepping forward like that was almost like the kiss of death… that was another challenge for me," he explained. "In all honestly, between my first two years, I was actually kicked out of school for various forms of activism. I was never expelled, just suspended for brief periods of time. That's the beginnings of how I transformed. Believe me, when I left high school, I was just an average kind of a person. I ran track more like a champion than I did the civil rights thing." He added that during his senior year at Delaware State he was nominated for the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship, an award for seniors who had the potential to be outstanding professors. He noted that it meant a lot to him and that it was a historical moment being a part of the first cadre of those chosen from historically Black colleges.

After attending graduate school, Pritchett worked for a fortune 500 company for two years. It wasn't until 1969 that Pritchett entered into what he called his inaugural year in higher education. He was the director of financial aid and the director of career services at Rider College (before it was a university). He stated, "Most of the students there had never seen anybody of an integrated nature in their lives at all. That was how I felt. The entire history and weight of race relations in this country fell on my shoulders." He mentioned that while teaching, "half of the class was looking straight through me. I had to stop and straighten a few things out about the psychology I was feeling…being invisible." Pritchett found himself speaking up on behalf of others at the college like the dean of the library who felt he couldn't fully express himself as a Jewish man. Pritchett said, "That's not what I was hired for, but that's how I learned the concept of allies although no one used that term then." He stayed at Rider for five years before moving on to William Patterson University where, for the next four years, he designed and taught Sociology courses. He then saw a very unique position at Seton Hall in what was then called the Black Studies Center. "It was a completely autonomous unit. It had a dean over it, about eight full-time people and 15-20 part time people. They wanted someone with a social science background," he explained.

Pritchett joined the Seton Hall family and immediately got to work, partaking in many of the foundational events that would steer the University through the process of integration. "Let me share this," he began. "Starting from '78, in intervals of every two to three years at Seton Hall, we had these major racial kind of confrontations that would occur. At night, the handful of us who worked there would meet to consider what we could all do, and just brainstorm what it would take. In the Black Studies Center, a couple times a semester on a Friday afternoon, we would get some sandwiches or some chicken, some beverages, and have some nice cool jazz music. We would put the word out and tell people to come over, that this is going to be like a nice home for [them] and we created what are now called safe spaces where we were all like family with each other."

Pritchett and I continued the discussion as he recalled students from the 70s-90s who marched all four years at Seton Hall for racial justice. He took me through the inception of campus groups like the Black Administrator Faculty Staff Association (BAFSA) and the Council Against Racial and Ethnic Discrimination (CARED), which were the steppingstones for Concerned 44, a student group established to voice the concerns of students of color and, overall, fight for equality and inclusivity on campus. From organizing protests and demonstrations to taking over President's Hall in 2018, these students challenged the very idea of what it actually meant to be seen, heard, and valued. He explained, "The group selected seven to be their negotiators who then met with five top administrators. At their third meeting, the [administration] asked me to join them to be the moderator. They also allowed people from the public to sit in. That was a proud moment. One of the women said she was just a mother who lived nearby and wanted to make sure the students were not being taken advantage of. That one almost made me cry. [The group] didn't really get a resolution, but they decided that they would continue to negotiate [their demands] without occupying the building." He continued, "I'll add that the seven students weren't all Black. I think that really shocked the administration as well. These students were very sharp. I was very proud of them."

While still circling the topic of race and justice, I transitioned into acknowledging that it was Black History Month. I asked Rev. Pritchett to talk briefly about what this time of the year signifies to him, and the importance of continuing initiatives and emphasizing Black history not just in February but every day. He said, "What I do now is really about what I was like as a teenager. You know, we would look in the mirror and we didn't like what we saw. We were made to think we were inferior. Our minds had been captured by the enemy so to speak. So, to me, it means covering that hole left in our soul as a result of living in a White-oriented America."

Itching to get to a few more questions before Rev. Pritchett would have to leave to teach a class, I asked him to speak briefly about his relationship with his students, and his advice for any young person looking to make an impact on their own campus regarding racial and social justice. "I would say be true to the struggle of your ancestors," he said. "I try to get students to remember that we live in the belly of the beast, and when that beast wakes up, we all might be gobbled up. So, I'm saying whatever you do, do it in excellence here so that nobody can take it apart." Elaborating more on mentorship, he shared a story about guiding some of his grad students through to their doctorate programs. "One of the young men entered in August of his freshman year. His father had died that same month of cancer. I told him if he needed a dad, or quiet time, he could come to my office. I supported him for four years. When he was a senior, he said, 'Pop, I got to get to my grad school interviews,' and I told him to schedule them on Fridays and I'd make sure I'm flexible to drive him. He went on to get his master's in divinity and now he has his doctorate and is teaching at various universities," he paused. "I share these stories because when I mentor, I mentor for life. That's one of my proudest moments… everything that was poured into me, I share openly with others."

Awards & Accolades

Community

- 2019 – American Conference on Diversity’s Humanitarian Award

- 2019 – New Jersey Black Issues Convention’s Community Change Award for Education

- 2019 – Faculty Achievement Award from Alpha Phi Alpha

- 2019 – Selected for the Educator Impact Award by Kappa Delta Pi International Honor Society

- 2016 – Lifetime Achievement Award from President Barack Obama

- 2015 - National Association for the Advancement of Colored People: New Jersey State Conference: Educator of the Year

Seton Hall

- 2020 – Honored as a Great Mind at Men’s Basketball Game

- 2008 – Employee of the Year

- 2003 – McQuaid Medal

- 1999-2000 – Faculty Pirate Pride Award

- 1997 – University Human Relations Citation