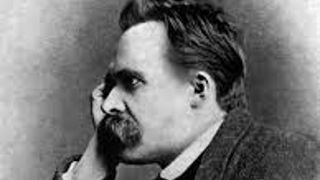

Inside the Core this Week, Friedrick Nietzche - Seton Hall University

Thursday, April 23, 2020

As we examine the ideas of Nietzsche, it is important to notice how, in his rejection of Judaism and Christianity (which he seems to conflate as essentially one religion), he focuses on specific aspects of these traditions, and this is what is most interesting in terms of the class. Though raised the son of a Lutheran pastor who died when he was young, Nietzsche was groomed to be a pastor himself. As a young adult, however, he rejected this goal for his life (held by his mother). However, because of his training in the Christian faith, he does have a good sense of what it means — sometimes it would seem better than many Christians.

For Nietzsche, the ideal person is the one who self-actualizes, who lives most fully and freely as him or her self. Believing in no god, he rejects the idea of revelation or of a moral law inherent in humans. His Geneology of Morals, excerpted in the Core II text, reveals Nietzsche's view that what we hold as good and evil grew out of the various human codes that created moral customs. First, he says, good meant noble, brave, aristocratic (not good in the sense that we normally mean the word — morally whole and compassionate, self-sacrificing). Nietzsche would say we have adopted a code created by what he calls the slave- priest class, which rejected the powerful and strong to affirm the weak. He accuses Christianity and Judaism as being religions of this slave-weak-priestly class of people, and says that they have labeled as evil those who do not fit this category — the rich, the powerful, and the strong. Is there any truth to this — from Nietzsche's perspective — accusation?

As Anthony Sciglitano, who teaches in the Core and was Director of the Core for many years, does when he teaches Nietzsche, it is very interesting to read Nietzsche's Geneology of Morals in conjunction with Jesus' Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew. Jesus does affirm "Blessed are the poor in spirit," and "blessed are the meek" (Matthew 5:1-10). Furthermore, Jesus says in Matthew 25, after describing service to various suffering and marginalized groups — the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger, the prisoner, the sick: "Whatever you did for the least of these brothers of mine, you did for me." In the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus, Jesus says the former will go to hell and the latter to heaven, because the former was blind to the plight of the poor man, suffering right at his gate (Luke 16:19-31). There truly is an implicit "option for the poor" in the Gospels.

Nietzsche rejected any such option. Speaking about "the Jews" but actually meaning Christians as well, Nietzsche describes this attitude: "the wretched alone are the good; the poor, impotent, lowly alone are the good; the suffering, deprived, sick, ugly alone are pious, alone are blessed by God, blessedness is for them alone — and you, the powerful and noble, are on the contrary the evil, the cruel, the lustful, the insatiable, the godless to all eternity; and you shall be in all eternity the unblessed, accursed, and damned!" (385). While the Judaeo-Christian tradition never says the poor, the weak, etc., are the only people who will be saved, the option for the poor inherent in the Gospels and in other places in the Bible suggests that God does have a special love for the poor, and that the rich need to be aware of them and care for them in order to be in harmony with the loving will of God. Nietzsche's depiction may be an exaggeration, but it gets at something that is at the heart of biblical teaching: human beings are not to be considered more worthy because of money, power, or status, but — instead — the values of the world are inverted. Many passages in the Jewish Bible, especially in the prophets, and a lot of the New Testament advocate this inversion of the norms of society (then as now).

Nietzsche also criticizes the advocacy of the gentle, "the meek" as Jesus calls them in the Beatitudes, over the more aggressive and violent. He uses the following analogy:

That lambs dislike great birds of prey does not seem strange: only it gives no ground for reproaching these birds of prey for bearing off little lambs. And if the lambs say among themselves: "these birds of prey are evil, and whoever is least like a bird of prey, but rather its opposite, a lamb — would he not be good?" there is no reason to find fault with this institution of an ideal, except perhaps that the birds of prey might view it a little ironically and say: "we don't dislike them at all, these good little lambs; we even love them: nothing is more tasty than a tender lamb" (393).

Nietzsche goes on to say: "To demand of strength that it should not express itself as strength, that it should not be a desire to overcome, a desire to throw down, a desire to become a master, a thirst for enemies and resistances and triumphs, is just as absurd as to demand of weakness that it should express itself as strength" (393). Ironically, there are some who call themselves Christian who advocate positions that sound like this one.

However, what kind of power actually is advocated by Jesus? It is certainly not weakness, though the lamb is used in the New Testament as an image for not only his followers but for himself — "Behold the Lamb of God." What does this mean? Jesus makes it clear that power for his followers must not follow the patterns of the world, clearly articulated by Nietzsche, who praised the Romans — who dominated the political world of Jesus' time — as an epitome of the kind of strength and power he admired. On the contrary, Jesus said, "The kings of the Gentiles lord it over them; and those who exercise authority over them call themselves Benefactors. But you are not to be like that. Instead, the greatest among you should be like the youngest, and the one who rules like the one who serves" (Luke 22:25-26). This kind of power, of non-violent love is, according to Jesus, stronger than the other kind of power, the kind that loves to overcome, threaten, dominate and ultimately destroy one's enemies.

So, the conversation, the dialogue between Christianity and Culture (in this case, Nietzsche) leads to some interesting conclusions. Both would conclude that Christianity is a church "for the poor" as Pope Francis calls it, and a religion of non-violence as opposed to aggression. But whether that is good or bad, is where the two part company. For Nietzsche, such an "option" is an abdication of the noble nature of the high-born and warlike natural man, whereas for Christ and his followers, as well as the Jewish teachers and prophets before him and after, strength comes from following the ways of the God who gives himself to his people over and over again, and asks them to do the same, especially for the "the least of them." This is especially true right now, in light of COVID-19 and the constant headlines that it is the poor who are suffering most, as always, from this latest crisis. To be truly great, in a way that is compatible with the teaching of Jesus in any sense, would be for our country to address the injustice and inequities that cause the unequal and excessive suffering for some more than others and respond with compassion and swift action.

Categories: Education