Inside the Core this Week: Justin Martyr and Augustine - Seton Hall University

Tuesday, February 4, 2020

Justin Martyr was born in Neapolis in Samaria, an area which today is called the West

Bank. Born into a pagan family, he studied diverse philosophies before becoming a

Christian at about thirty, feeling that Christianity fulfilled, as no other philosophy

did, the longing for truth that had prompted his searching. However, unlike Tertullian

(who famously said, "What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?"), Justin instead sought

to reconcile what was best in prior and contemporary pagan philosophies with Christianity.

Arguing that former philosophers were essentially "Christians before Christ," so long

as they searched and argued for the truth, he was more in line with modern perspectives,

like those expressed in Nostra Aetate, that all that is good and true in any religion

should be affirmed. Justin even used terminology like Logos, meaning "Word" or perhaps

"Wisdom" or "Truth," to describe the nature of Christ – intentionally using a concept

familiar to Greek philosophers in order to relate to them meaningfully. However, despite

his own open-mindedness, Justin encountered persecution directed against Christians,

as a minority group feared and hated as being subversive and a threat to the status

quo. He was beheaded in the year 165.

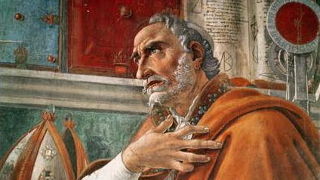

Augustine, born in 354 in Thagaste, Algeria, North Africa, also studied philosophy,

but particularly focused on rhetoric. Though his mother was a Christian, and he was

trained in that faith, his father was a pagan. With Christianity legalized in 313

by the Emperor Constantine's Edict of Milan, Augustine came of age in a world much

like ours – eclectic, hedonistic, and materialistic. Drawn into the seductions around

him, he indulged in stealing (the famous pear tree incident), lust, intellectual pride,

and worldly ambition. However, the search for truth and the longing for love, ultimately

God's love, eventually led him to conversion to Christianity. He says in the Confessions, "Our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee." In his famous City of God, which we read excerpted (Book XIX) in Core II, Augustine distinguishes the difference

between the earthly city and the heavenly city, the City of God. The bond of the City

is ordered love (meaning love that reflects the order of creation), bringing peace

and harmony. Augustine, though rejecting the teaching of rhetoric and pagan literature,

uses the skills acquired in his background to make the points in his famous treatise.

Love is central to the life of the City of God on earth (as it is in heaven), and

ordered love means that one loves appropriately, according to the will of God. Examples

would be loving one's child more than one's pet, or loving one's friend more than

one's status. There is a hierarchy of values in Augustine's view, and loving rightly

is part of loving at all.

Both Augustine and Justin lived at times of transition in the Roman Empire. For Justin,

it was a time where Christianity was expanding, an exciting time, but a dangerous

one. For Augustine, the dangers were more spiritual, and his search for truth was

complicated by desires for other, lesser goods. He came to peace after a spiritual

journey that took him from one continent (Africa) to another (Italy in Europe) and

back (to Africa) again, and through many philosophical and religious positions. When

he finally became a Christian, he had found what he was looking for in the many venues

in which he searched.

Today we live in a society that is both complicated and eclectic, but also one that

is transitional, and where people who are different can be seen as suspect and even

hated (as were the early Christians). In fact, in many parts of the world people are

dying for their faith as they did in the time of Justin. But in our culture, like

that of Augustine, the dangers may be in some ways worse because they are more subtle.

Overall, reading these texts, ancient as they are, can be very important and relevant

to life in the world of 2020.

Categories: Education