Students Read Simone Weil - Seton Hall University

Friday, May 1, 2020

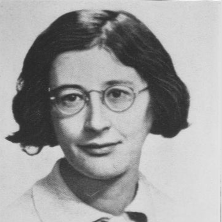

Simone Weil

This is the last full week of classes, and many Core II students may be reading Simone Weil, the French philosopher and mystic who wrote Waiting for God, Gravity and Grace, and other works, including "Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God" (in our Core II textbook). This wonderful, concise essay describes how the work done for class can help us on the road to sanctity, if we approach it the right way. This may sound strange, but the key thing for Weil is attention.

Whenever we pay attention to something, anything, in a class, Weil argues that this prepares us to pay the ultimate kind of attention that we pay to God and to other people (when they need our love and compassion, a listening and attentive ear). Even classes that we are not to our taste or even extremely difficult for us can help us if we give them our full attention. In a sense, we are honing our skills for (in Weil's opinion) the more important work of loving God and neighbor. A very successful scholar herself, Weil is not negating education. However, she is putting it in the larger context of our relationships with God and other people.

Born in Paris in 1909, Weil was raised in a not especially religious Jewish family. She attended the Ecole Normale Superieure, where she was an outstanding scholar. Her intellectual interests led her to read Pensees by Blaise Pascal, and eventually she was drawn to a belief in Christ. Before she developed the habit of regular praying, she would recite George Herbert's poem "Love III" repetitively, like a prayer. Once, when doing this, as she wrote to a priest, her friend, Fr. Perrin: "Christ himself came down and took possession of me." Her intense spiritual life informs the way she came to understand study as an exercise leading to holiness.

Toward the end of her life during World War II, Weil's family fled France to escape the Nazis. She gave half of her food rations to the poor, and was suffering from lack of food and poor health. Simone Weil died in 1943 in London.

"It is the part played by joy in our studies that makes of them a preparation for spiritual life, for desire directed toward God is the only power capable of raising the soul. Or rather, it is God alone who comes down and possesses the soul, but desire alone draws God down. He only comes to those who ask him to come; and he cannot refuse to come to those who implore him long, often, and ardently" (580) Simone Weil.

Love (III)

By George Herbert

Love bade me welcome. Yet my soul drew back

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning,

If I lacked any thing.

A guest, I answered, worthy to be here:

Love said, You shall be he.

I the unkind, ungrateful? Ah my dear,

I cannot look on thee.

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

Who made the eyes but I?

Truth Lord, but I have marred them: let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.

And know you not, says Love, who bore the blame?

My dear, then I will serve.

You must sit down, says Love, and taste my meat:

So I did sit and eat.

Source: George Herbert and the Seventeenth-Century Religious Poets (W. W. Norton and Company,

Inc., 1978)

Categories: Education