Inside the Core- Core I students read Plato's Apology - Seton Hall University

Friday, September 11, 2020

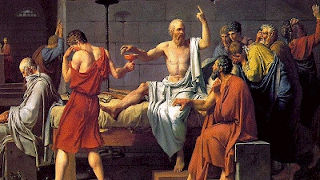

Death of Socrates by Jacques Louis David, 1787.

This week students in Core I are reading Plato, and one of these texts is the Apology. This famous speech is presented as Socrates' defense at his trial for "corrupting the youth and introducing strange deities" (or atheism). Clearly, Socrates is not apologetic in the colloquial use of the word; his apologia, or explanation of his actions and beliefs, is really a strong statement that he will in no way stop the kind of teaching and philosophical inquiry which had made him so many and such strong enemies. Instead, it is a powerful argument for why, as he believed, he was right to continue, even if it meant his death.

A few key points are important to recognize. First, though the result of the trial was unfavorable to Socrates, as we discussed in my own Journey class, his speech was a success because he proved his opponents wrong, and posterity (even to this day) is reading his argument, and probably the vast majority of these readers would be convinced by at least large portions of it. He was right to continue following his moral and ethical beliefs, despite the enormous pressure to back down. He was right to choose virtue and enlightenment over worldly success, power and money. He was right to choose death over acting against his conscience, what he described as the leading of divine inspiration, as "the unexamined life is not worth living," as he so famously said.

Second, it is important to realize that, while this trial resulted in what most of us would agree was an unjust sentence, the concept of having a trial was a new and much more democratic practice than simply having a ruler decide if an individual deserved to die or not. Aeschylus' play The Eumenides mythically depicts the origin of Athenian trials, in the case of Orestes, who murdered his mother, Clytemnestra, in revenge for her and her lover's killing of his father, Agamemnon, upon his return from the Trojan War. Up until this time, personal revenge was accepted and acceptable. The new trial system, it was hoped, would bring in a more just way of handling crimes than personal vendetta or tyrannical command. As it turns out, in the play Orestes is acquitted, by a mixed jury (half in support of his punishment, and half against, but with "the vote of Athena" swaying the verdict in his favor). In Socrates' case, the jury was more clearly against him, hence his sentence of death by drinking hemlock, but it was by no means a large majority that decided his fate. The vote was 280 for his death and 220 against it. Juries in Athens were very large! But Socrates himself was surprised that so many among the jury supported him. Among those supporters was Plato, his student, who recorded what happened (no doubt with some embellishment and interpretation), but clearly giving a sense of what went on, including even Socrates' asking not to be interrupted as he made his case.

Third, and this is very important in today's world where legal and criminal justice issues are in the forefront of social justice concerns: though a jury makes for a more just situation that a simple king's verdict or personal vengeance could possibly do, it does not by any means ensure justice. Socrates' situation is a case in point. The bias and resentment of many among the jury, the falsehoods spread by his enemies, clearly persuaded enough of the jury to vote against him, despite, as seems quite clear to most of us, the fact that this man did nothing to deserve death. In my class we discussed how issues of bias today, particularly racial bias, affect juries that disproportionately condemn people of color. We viewed an interview with Bryan Stevenson, the author of Just Mercy and the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Al. Stevenson, who is also depicted in the film Just Mercy based on his book, went South in 1985 as a recent Harvard Law School graduate in order to take on cases of inmates on death row, who had been unjustly tried. The film depicts a particular case of a man named Walter McMillian, who had been condemned to death row even prior to his trial, for a murder occurring while he was eleven miles away at an event to raise funds for his sister's church. The word of the many people who were with him was discounted, and the testimony of one questionable witness prevailed. Stevenson's work on this case and many others shows that jury trials, particularly when affected by systemic racism, can lead to unjust sentences, in today's world as was the case in Socrates' time (though it was not racism, of course, but a dislike of his philosophical views that led to his death). As Bryan Stevenson says in the interview, we should not be asking whether someone "deserves to die," but whether we, as a society, "deserve to kill." The flawed trial of Socrates and the many overturned cases of those exonerated through the efforts of Bryan Stevenson raise this serious question of whether human beings ever have the moral or legal right to take the life of another person. Personally, I (along with Pope Francis and many in the Church) would argue, we don't.

Bryan Stevenson, author of Just Mercy and founder of Equal Justice Initiative

Clearly, the ancient texts in the Core relate to contemporary situations regarding this issue and many others. Though social situations and political institutions have drastically changed in the more than 2300 years since the death of Socrates, human nature and potential for bias remain part of the problems with juries obtaining the death sentence for any individual. Bryan Stevenson majored in philosophy prior to attending law school. His work and the story of Socrates show the important link between philosophy, along with ethics and religion, and the critical issue of legal justice.

Categories: Faith and Service