Inside the Core

Friday, September 15, 2023

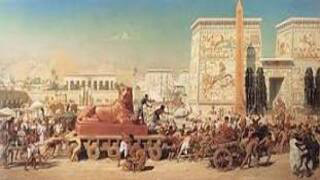

Israel in Egypt (Edward Poynter, 1867), courtesy of Wikipedia

This week and next week, students in Core I will likely be moving from the study of works by Plato to the Hebrew Scriptures, specifically Exodus and the Book of Ruth. How fitting that we move into the study of these scriptural texts right when Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, is celebrated. Any new year, whether secularly or religiously defined, is a time to take stock and to rethink perspectives. In light of one of the texts Core I students read by Plato, the Allegory of the Cave, wherever we are locked into false beliefs, believing shadows to be reality, we need to move out of the cave into the sunlight (i.e. the truth) to see what is actually happening, what is true, what is right. In the book of Exodus, we get some interesting insights into what is true, real, and morally right regarding one particular issue very relevant to our times—the plight of the alien or the stranger in a country not their own and how such people ought to be treated.

In Exodus we learn that a new Pharoah arose in Egypt with no memory of Joseph, the Hebrew leader who saved the Egyptians during a severe famine and brought his family into Egypt to reside in Goshen. This new Pharoah began to fear the Hebrews, as they grew numerous, saying, "Come, we must deal shrewdly with them or they will become even more numerous and, if war breaks out, will join our enemies, fight against us and leave the country" (Ex. 1:10). This fear, unwarranted as it apparently was as the Hebrews had shown no sign of being traitorous or treacherous, leads to their enslavement and, ultimately, to the killing of the Hebrew baby boys (a fate from which Moses is providentially saved, through the kindness of Pharaoh’s daughter). When the Lord uses Moses to free his people, he enjoins them to remember their time as strangers, aliens in the land of Egypt, therefore, showing compassion to strangers and aliens among them. In Leviticus and elsewhere, he reminds his people: "The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt; I am the LORD your God" (Lev. 19:13).

"Naomi and her Daughters-in-Law" (Chagall, 1960), courtesy of Womeninthebible.net

The book of Ruth, also required in Core I, similarly deals with the plight of aliens, in this case refugees, as Mary Balkun Ph.D. presented to faculty several years ago. Elimelech and his wife, Naomi, along with their two sons, Chilion and Mahlon, leave Israel for Moab due to a famine. After the sons’ marrying two Moabite women, Ruth and Orpah, all three men die, leaving three widows, a vulnerable position in the ancient world. These Moabite women treated the alien family into which they married kindly, as Naomi acknowledges to her two daughters-in-law. When the famine in Israel ends and Naomi decides to return to Israel, Ruth will not leave her side but returns with her mother-in-law. Her story, told respectfully to her and engagingly about the two women’s situation, describes Ruth’s gathering gleanings in the field of Boaz, gleanings required by the Law to be left for aliens and other poor people. When Boaz learns of Ruth’s kindness and loyalty to her mother-in-law, he is impressed, so much so that he eventually marries her (though, no doubt, other factors, like his being next of kin and perhaps even a strong attraction, likely had something to do with it as well). This stranger, Ruth, a Moabite, from a tribe generally despised by the Israelites, is held up by the writer of sacred Scripture as a role model, someone to be admired, who becomes, in fact, the grandmother of the great King David, and, very important to Christians, an ancestor of Jesus, mentioned in his genealogy recounted in Matthew 1.

So, what cave, to use Plato’s terminology, might we need exit in order to move into the light of these Hebrew Scriptures for the New Year? There are many lessons in Exodus and the Book of Ruth, but one key point made by both is that aliens, sojourners, strangers, should be welcomed and respected, their plight seen with compassion and empathy, for "you were aliens in the land of Egypt." That ancestral memory, relevant not only to Jews but to anyone claiming an Abrahamic heritage of faith, ought to inform our attitudes to refugees and migrants in our current day. This topic is one of many current issues that the ancient readings in the Core speak to powerfully and meaningfully, as much today, as when they were written.

Categories: Faith and Service