Core II Students Read Karl Marx in Dialogue - Seton Hall University

Thursday, April 2, 2020

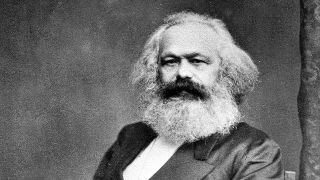

First, let's look at differences. Karl Marx, with Friedrich Engels, wrote The Communist Manifesto in 1888. The world was quite different then, but there was much economic inequality that was, in some ways, global in scope as there is today. Marx did much of the writing in the British library in London. As Msgr. Dick Liddy said once in a class that I was co-teaching with him in Oxford, Marx impacted the world hugely by sitting in a library studiously working. His point was meant as an encouragement to students because few political writings have impacted the world as much as this small manifesto, written in a quiet scholarly setting. The twentieth century would see this impact in Russia, China, and most of Eastern Europe. On the other hand, Evangelii Gaudium was written by Pope Francis in 2013, his first year of papacy; though written quietly, the book was coming from a source, the Vatican, with global impact right from its first publication. Its focus, as indicated by its Latin title, is the joy of the gospel. This focus on faith is a drastic difference from the secular assumptions, essentially atheism, that underlie Marx's work.

In a short article like this I can't possibly explore the complexities of all that Marx is expressing, but, to put it simply, he wants workers to have rights and ownership over the means of production. This would alleviate the important problem of alienation that developed as industrialization replaced the small guilds that represented various crafts and other positions of the merchant class in the Middle Ages, as Marx explains. Workers in factories do not get to see a final product or gain personal satisfaction from their work, as would a craftsperson making a shoe or glass-blowing a vase or creating breads. The bourgeoisie own the factories, and they reap the benefits, that the proletariat (the workers) make possible but do not get to enjoy.

Pope Francis also is concerned about the marginalization of the lower classes, the working class, and perhaps especially those even lower on the social strata — those not working, left on the streets to struggle and perhaps die. The Holy Father, while never advocating a complete rejection of private property, still less the atheism implicit in Marx's text, strongly argues for a shift in our perspective toward those left out of the system — a shift inspired by the Gospels and the specific teachings of Jesus regarding the poor. He says, "Our preferential option for the poor must mainly translate into a privileged and preferential religious care" (101). He makes a strong point regarding inequality: "As long as the problems of the poor are not radically resolved by rejecting the absolute autonomy of markets and financial speculation and by attacking the structural causes of inequality, no solution will be found for the world's problems or, for that matter, to any problems. Inequality is the root of social ills" (102). Saint John Paul II makes a related point: "We have seen that it is unacceptable to say that the defeat of so-called ‘Real Socialism' leaves capitalism as the only model of economic organization. It is necessary to break down the barriers and monopolies which leave so many countries on the margins of development, and to provide all individuals and nations with the basic conditions which will enable them to share in development" (Centessimus Annus, 1991). Both Holy Fathers are expressing a concern about a secular idolatry of the marketplace that places monetary gain above all other considerations.

Pope Francis closes this section of Evangelii Gaudium with a call for prayer for political leaders: "Why not turn to God and ask him to inspire their plans? I am firmly convinced that openness to the transcendent can bring about a new political and economic mindset which would help to break down the wall of separation between the economy and the common good of society" (104). In these times of challenge due to COVID-19 and the enormity of its impact, it is good to look at words of hope, even if about another global problem. As St. Paul (another writer in Core II) says, "…hope does not disappoint, because the love of God has been poured out within our hearts through the Holy Spirit who was given to us" (Romans 5:5).

Categories: Faith and Service